This is the third in a Governing series on a historical look at the Supreme Court to coincide with nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation process, which continued this week before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

With hearings under way to fill an opening on the U.S. Supreme Court, it may be useful to look back on the history of court appointments. “Appointments,” Thomas Jefferson said, “and disappointments.”

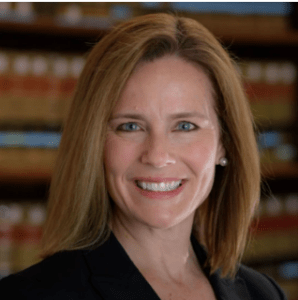

Since 1789, 115 individuals, nearly all of them white, most of them men, have served on the U.S. Supreme Court. Thus far, only five women have served on the court, two African Americans (Thurgood Marshall and Clarence Thomas) and one Hispanic (Sonia Sotomayor). No Native Americans have been appointed. Although the great majority of justices (91) have been Protestants in one form or another, 15 Catholics have served (now including Amy Coney Barrett), including three chief justices. Eight justices have been Jewish. No Muslims have served on the court.

If confirmed, Ketanji Brown Jackson, President Biden’s nominee to fill Justice Stephen Breyer’s seat, would be the sixth woman and the first Black woman to serve on the nation’s highest court.

Skewed Representation — Ethnicity, Education, Geography, Gender

The majority of justices have come from the northeastern quarter of the United States. Ohio has produced the most, with 10, followed by Massachusetts with nine; Virginia, eight; Pennsylvania, Tennessee and Maryland with six; Kentucky and New Jersey with five; and California, Illinois and Georgia, four. Three states have produced three justices: Connecticut, South Carolina and Alabama. Six states have produced two. Eight states one. Six justices were born outside the United States. The most recent was Felix Frankfurter, born in Vienna, Austria, who served between 1939 and 1962. Nineteen states have never produced a Supreme Court justice.

The court can hardly be said to be representative of the lives of most Americans. The current court consists of four Harvard Law School graduates, four Yale, and one (Amy Coney Barrett) who studied law at Notre Dame. Historically, 21 justices have studied law at Harvard, 11 at Yale, seven at Columbia and three at the University of Michigan, with a scattering of dozens of others from law schools around the nation, including Northwestern, Stanford and University of Virginia. It is virtually impossible to conceive of a graduate of the University of North Dakota Law School or Brigham Young Law School becoming a Supreme Court justice. In a nation that thinks of itself as a meritocracy, merit has a way of locating itself in a handful of elite institutions that most Americans can never attend.

Neo-Constitutional Norms

Five justices, most of them appointed early in the history of the court, had no formal legal training whatsoever. The Constitution does not specify any educational requirement for Supreme Court justices or even a legal background for that matter. Theoretically, a farmer or electrician could be appointed, though today’s small C constitution (the tenacious norms of American public life that have nearly constitutional status) would certainly preclude anyone without elite legal training, even if that nominee were Mother Teresa or Carl Sagan.

“Few die and none resign.”

— Thomas Jefferson

Once confirmed by the U.S. Senate, justices serve for life. Despairing of life-tenured justices, Thomas Jefferson famously said, “Few die and none resign.” The average tenure has been 16 years, though that number is bound to go up as justices are appointed at an earlier stage in their lives and the longevity of First World people continues to rise.

Life Tenure Is Longer Than It Once Was

Life tenure meant one thing in 1787, when the Constitution was written, something quite different in the mid-21st century. In the Age of Jefferson, life expectancy was under 39 years (largely due to high infant mortality rates). By 2020 it was 78.9 years in the United States. When George Washington or Andrew Jackson appointed a Supreme Court justice who was in his 40s or 50s, that man could be expected to live no more than another 10 to 20 years. Today, a young justice can be expected to live far longer than the president who appointed her or him, and longer than most members of the Senate that confirmed the appointment.

On the current court, Justice Clarence Thomas has served for 31 years. He is 73 years old. Stephen Breyer has served 28 — he’s 83. Chief Justice Roberts has served 17 — he’s only 67. Samuel Alito has served 16 — he’s 71. Sonia Sotomayor has served 13 — she’s 67. Elena Kagan has served 12 — she’s a youthful 61. Neil Gorsuch has served just five years, but he’s only 54 years old. Brett Kavanaugh has served four, and he’s only 57. And Amy Coney Barrett, who has only served two years so far, is just 50. Assuming that the most recent four justices live another 30 years and Barrett perhaps 40, we are in for some very long tenures. Jefferson, who loved statistics, argued that a generation lasted approximately 19 years. Today, most actuarial experts cite 20 to 30 years as the lifespan of a single generation. Under either metric, many justices serve longer than a generation of the American people, which Jefferson regarded as fundamentally wrong, not to mention undemocratic. “The earth,” he said, “belongs to the living not the dead.”

The longest serving associate justice so far was William O. Douglas. He retired in 1975 after serving 37 years, seven months and eight days on the bench. That record will soon be eclipsed. The shortest tenure was John Rutledge (of South Carolina) who served one year and 18 days. A handful of others, including James F. Byrnes and Thomas Johnson, have served fewer than three years on the court.

The youngest justice ever appointed was Joseph Story, who was merely 32 years old at the time of his appointment, by James Madison, in 1812. He served 33 years. The oldest justice at the time of his appointment was Charles Evans Hughes, who was 67 when nominated by Herbert Hoover in 1930. He served 11 years. The record for being the oldest person to have ever served on the court remains with Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who stepped down in 1932 just short of his 91st birthday. More recently, Justice John Paul Stevens left the court in 2010, two months after turning 90. Critics of life tenure wonder at what point an elderly person loses touch with the lives of the majority of the American people.

Retirement As Redress?

In the past hundred years, most Supreme Court justices have retired before they died. The deaths of sitting justices William Rehnquist in 2005, Antonin Scalia in 2016 and Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2020 represent rare exceptions. Between 1789 and 1900, 38 of the 57 Supreme Court justices died while in office (67 percent). But since 1900, 39 of the 46 justices who have served left in retirement (84 percent). For the half-century between 1955 and 2005, there was not a single death of a sitting Supreme Court justice.

Supreme Court justices are granted life tenure “on good behavior.” That strange phrase does not mean building houses with Habitat for Humanity, driving the speed limit or volunteering at the local food bank. Most constitutional historians agree that the good behavior clause simply indicates that judges are not appointed to their seats for limited terms, and they cannot be removed at will. In other words, the phrase is essentially meaningless.

So far, there has never been a successful impeachment of a Supreme Court justice. In fact, the only justice every impeached was Samuel Chase (served 1796-1811). Chase was a high-toned Federalist who browbeat lawyers from the bench, bullied juries and instructed them how to decide cases and delivered long partisan diatribes in court. Strangely enough, he had also been a signer of the Declaration of Independence. President Thomas Jefferson, who was no friend to the judiciary, convinced his friends in the House of Representatives to impeach Chase in 1805, in part because of Chase’s partisan and aggressive handling of trials brought on by the Sedition Act of 1798. And though nobody doubted that Chase had strayed far from the standard of impartial justice, he had not committed any “high crimes and misdemeanors,” and he had not taken bribes. He was therefore acquitted by the U.S. Senate. Afterward, Jefferson called the impeachment clause of the Constitution a “mere scarecrow” and a “bungling way” of trying to chasten the court. Most historians agree that the acquittal helped solidify the independence of the judicial branch from the more political branches of the U.S. government.

One of the most delicious ironies of the Chase impeachment was that the Senate trial was presided over by Jefferson’s disgraced Vice President Aaron Burr, who had killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel in New Jersey months earlier, in the summer of 1804. One of the wags in Congress quipped that while it is usual for the judge to try the murderer, here in our happy republic we witness the murderer trying the judge!

After that, from 1805 until today, no Supreme Court justice has ever been impeached, though partisans have called for the impeachment of dozens of justices, including most recently Chief Justice Roberts, for seeming to side with the Obama administration in upholding a key provision of the Affordable Care Act.

Life Means Life

“Appointments and disappointments.”

— Thomas Jefferson

So, to put it in a nutshell, once they are in, they’re in! That is one reason why the nomination and confirmation process have become so politically intense. The stakes are enormously high. Nine unelected individuals decide questions of monumental importance for a third of a billion citizens.

You can hear more of Clay Jenkinson’s views on American history and the humanities on his long-running nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, “The Thomas Jefferson Hour,” and the new Governing podcast, “Listening to America.” Clay’s new book, “The Language of Cottonwoods: Essays on the Future of North Dakota,” is available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble and your local independent book seller. Clay welcomes your comments and critiques of his essays and interviews. You can reach him directly by writing cjenkinson@governing.com or tweeting @ClayJenkinson.