The Old Lion is Dead

Jan. 6, 2019 — Theodore Roosevelt died 100 years ago today. He was just 60 years old. As he said when he determined to run South America’s River of Doubt against the stern warnings of the American Museum of Natural History, “Tell Osborn I have already lived and enjoyed as much of life as any nine other men I know; I have had my full share, and if it is necessary for me to leave my bones in South America, I am quite ready to do so.” Five years later he died at his beloved home on Long Island, N.Y.

The books he read as a sickly child convinced him that life was an adventure that must be lived heroically. If ever a man had gusto it was Theodore Roosevelt. He bounded up the stairs of the public buildings where he worked — as police commissioner, U.S. civil service commissioner, governor of New York, vice president and 26th president of the United States. He climbed the Matterhorn on his honeymoon. He trudged for 60 miles without sleep through gumbo and ice behind the thieves who stole his boat in the Dakota Badlands. Even the sheriff in Dickinson, N.D., wondered why he didn’t just shoot or hang them, but that was not the Roosevelt way. When he brought the outlaws to justice, in April 1886, the doctor who attended to his battered feet reported that “he was all teeth and eyes,” fatigued beyond measure but boyish and innocent and somehow irresistible.

Roosevelt was so much larger than life that the term seems insufficient to capture his essence. A visitor said, “You go to the White House, you shake hands with Roosevelt and hear him talk — and then you go home to wring the personality out of your clothes.” He set the record for shaking hands on a single day — 8,510 of them on New Year’s Day 1907 at the White House. He had himself dangled upside down over a cliff in Idaho to take a photograph of a waterfall. When they couldn’t haul him back up, he eventually cut the rope and plummeted toward the riverbed like a sack of potatoes. Fortunately, a tree broke his fall somewhat, but even Roosevelt said he was rather grievously damaged in the incident.l

He had a nearly eidetic memory, and he read something like a book a day. He lectured in German universities in German about German literature in 1910. When Columbia’s Nicholas Murray Butler wrote to ask him what he had been reading lately, President Roosevelt sent a list of more than 200 books, including classics of English, Russian, German and American literature. A Finnish woman who had dinner at the White House was stunned when he proceeded to give her a lecture on Finnish saga, quoting from “The Kalevala.” On the River of Doubt in 1914, Roosevelt read through the extensive portable library he carried with him into the Amazon jungle, then — in desperation — wound up borrowing his son Kermit’s anthology of French poetry, in French, even though he did not much care for French poetry. No president in American history mentions reading and books as often as Roosevelt, not even John Adams or Thomas Jefferson.

He was the most prolific writer in presidential history. He wrote approximately 40 books, not with the help of teams of researchers and ghost writers, but in his own hand, in clear, unpretentious, muscular prose. He also wrote more than 150,000 letters, innumerable articles and op-ed pieces and forewords to the books that embodied his interests and world view, including John A. Lomax’s “Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads” and Edward S. Curtis’ “The North American Indian.”

Theodore Roosevelt was a statesman, a politician, a reformer, a rancher, a cowboy, a civil servant, a big game hunter, a soldier, a writer, an explorer and a family man.

Almost before anyone else, Roosevelt realized that the United States was going to become the most important nation in the world and that the 20th century was going to be the American Century. He carried the American people into the 20th century, sometimes kicking and screaming, advocated and helped build a big navy, sent the entire U.S. Navy on a round-the-world friendship cruise, successfully brokered an end to the Russo-Japanese War, formulated the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, dug the Panama Canal and won the Nobel Peace Prize, the first American president to do so.

Of course, he had faults. He could be a bully. He could be righteous. As a young man, he flirted with the eugenics movement. He said nasty things about American Indians. He was paternalistic with respect to African-Americans and, in 1906, he not only jumped to unjust conclusions about a race incident in south Texas but stubbornly refused to revisit the incident when it became clear to everyone, including himself, that he had been unfair. He demonized his political enemies. He had a Manichaean view of life, assumed always that he was on the side of virtue. Speaker of the House Thomas Reed said, “What I most admire about you, Theodore, is your original discovery of the Ten Commandments.”

Still, he was unhesitatingly faithful to his wife, Edith. He was incapable of personal corruption. He spoke his mind forthrightly, even when he knew his views were unpopular. In a libel trial that might have bankrupted him, warned that he must not comment about the sinking of the Lusitania before a largely German jury rendered its verdict, TR spoke his mind with his usual strenuosity — and won the case. He sued an upstate Michigan newspaper publisher for writing that he was frequently drunk in public — gathered an all-star cast of character witnesses from around the country to defend his character, took the stand and gave an interminable monologue outlining all the drinks he had ever consumed, won the expensive case and, when he was asked by the judge what damages he sought, asked for the statutory minimum six cents.

He fought for the United States in the Spanish-American War in Cuba, offered to fight in half a dozen other potential American conflicts during his lifetime and went hat in hand to his enemy President Wilson in 1917 seeking one last chance to lead a crew of harum scarum Rough Riders into the fighting fields of France. Wilson told him he was too old, war was no longer a romantic business, that he should leave World War I to the professionals. Bitter, aware that his vitality was spent, he pushed his four sons into the war and insisted they find their way to the front. All were wounded. One, his youngest and favorite, Quentin, did not return.

TR became the Theodore Roosevelt of American memory (and mythology) out in the Badlands of North Dakota. Along the banks of the Little Missouri River, in a broken landscape that reminded him of the poetry of Edgar Allan Poe, Roosevelt underwent a transformation from a physically fragile, socially conscious dandy and New York “dude” into America’s greatest exemplar of the strenuous life. Out among the buttes and the cottonwoods, Roosevelt learned to admire the men and women of the American heartland: honest, unpretentious, not particularly refined, outstanding in a crisis, solid, courageous and hard-working. It can be said that Roosevelt’s Square Deal was born on the frontier along the Montana-Dakota border. “It was here,” he said in 1900, “that the romance of my life began.”

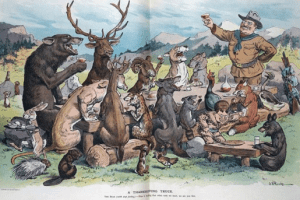

Along the way, and partly at his Elkhorn Ranch in the Dakota Badlands, Roosevelt became the greatest conservationist in American presidential history. He invented the National Wildlife Refuge System, established five National Parks, set aside 150 million acres of National Forest, designated the first 18 National Monuments, including the Grand Canyon, created national game preserves, co-founded the Boone and Crockett Club and played a key role in saving the buffalo from extinction.

He was an indefatigable, unrelenting, sometimes exhausting figure in American life. In the course of his 60 years as he reveled in the glory of work and the joy of living, he did a great deal of unnecessary damage to his body. The two culminating blows were an assassin’s bullet in the last days of the 1912 Bull Moose campaign and an array of fevers and affections that finally put him on his back in the Amazon jungle two years later. The River of Doubt shortened Roosevelt’s life by a decade, his sister Corinne said. Still, when he died quietly in his sleep at Sagamore Hill, Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, said, “Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight.